Missionaries and colonists once referred to the coastal areas of West Africa as White Man’s Grave. Mortality rates were exceptionally high, and a unicellular protozoan parasite known as plasmodium falciparum was one of the main reasons why.

Several hundred years later, plasmodium falciparum – the most dangerous and most commonly found strain of malaria in West Africa – continues to present serious health risks to travelers and locals alike.

Malaria remains endemic throughout the entire region. This map is somewhat dated, but you can easily see that all the countries in West Africa are affected.

While there is no vaccine for malaria, significant improvements have been made in prevention and treatment, resulting in far fewer serious and fatal cases.

Preventing Malaria 101

There are two ways to prevent malaria infection: taking a medicinal prophylactic and avoiding mosquito bites. Avoiding bites is impossible, but it is worth talking about how to get less of them.

- Use a mosquito net. This is number one for a reason. Most hotels and guesthouses have them, but if they don’t, a mosquito net typically costs $6 or less in the local market. Without a mosquito net, you will get bit continuously throughout the night.

- Use decent insect repellant. Look for DEET or Picaridin as active ingredients. Oil of lemon eucalyptus is also useful. Apply the repellant liberally where you find you are most often bit. Legs and ankles are often most vulnerable. Check out this article for some great recommendations on quality repellants.

- We could also tell you to wear long sleeves, pants and socks, but if you are in the middle of the hot season in Mali, for example, this is not realistic advice.

Prophylaxis

There are three drugs that are widely considered to be effective in the prevention of malaria in West Africa. All of them have known side effects, but two of the drugs are far more notorious in this regard.

Mefloquine (brand name Lariam)

Mefloquine is very effective as a prophylactic, and you only have to take one pill a week. You do, however, have to take mefloquine two weeks before your trip and for four weeks after you return. It also has the most alarming side effects out of the three drugs. Notably, it has been linked to vivid nightmares, depression and episodes of psychosis.

“A boxed warning, the most serious kind of warning about these potential problems, has been added to the drug label. FDA has revised the patient Medication Guide dispensed with each prescription and wallet card to include this information and the possibility that the neurologic side effects may persist or become permanent.”

That is from the New York Times after the FDA revised the warnings on mefloquine. On a personal note, I took Lariam for several months in 2005, and the nightmares I had, especially around the time I took the pill, were like nothing I’ve ever experienced.

Doxycycline

Doxy is effective, and it is the cheapest of the malaria prophylactics. It is an antibiotic that is used for a variety infections as well as for the treatment of acne. It needs to be taken two days before your trip begins and for four weeks after you return.

Doxy has its own side effects, though, and personally I would never take it again. I developed severe acid reflux while taking it for malaria in 2010. The most common side effects are increased photosensitivity, a skin rash, and acid reflux. It is worth noting that plenty of people take doxy with absolutely no issue. I was not one of them.

Atovaquone/proguanil (brand name Malarone)

Malarone is taken once daily, starting two days before your trip and continuing for seven days after you return. It is considered to be effective as both a prophylactic and a treatment. Furthermore, it has the lowest incidence of side effects amongst the three drugs. It is the antimalarial that is most often prescribed by the Peace Corps for this very reason.

While Malarone may be expensive to purchase in your country of origin, you can always buy a short-term supply and then re-stock once you are on the ground in West Africa (it can be purchased at just about any pharmacy).

Verdict: we are fans of Malarone for the limited side effects. That said, we are not doctors, and you should visit a travel health clinic and consult a doctor before taking any one of these drugs.

What if I’m traveling long-term? Should I still take a prophylactic?

This is a tough call, and one that you should make with your doctor. I no longer take malaria prophylactics, but I stopped traveling and permanently based myself here. Any antimalarial will be taxing on your liver if taken long-term, and doxy is an antibiotic so it is more or less wiping out all the beneficial bacteria in your gut while it’s protecting you from malaria.

Personally, I would take prophylactics if I was traveling anywhere from one day to one year. Beyond that, I would consider coming off them and traveling with a treatment option (we will get to this later) while also trying to avoid bites as much as possible.

My decision would also depend on where I am traveling. If I was mostly in rural areas that were filled with rice fields and canals, I would likely stay on the prophylactics. If I’m in a city, where the incidence of malaria is often lower, then I would stop taking them. Once again, be sure to talk to an actual doctor before making your decision.

What happens if I get malaria?

All of the prophylactics are effective, but none of them are foolproof. They will, however, mitigate the symptoms and hopefully prevent a case of severe or complicated malaria. If you do come down with malaria, you will likely experience one or all of the following three symptoms: Fever, chills, and headache.

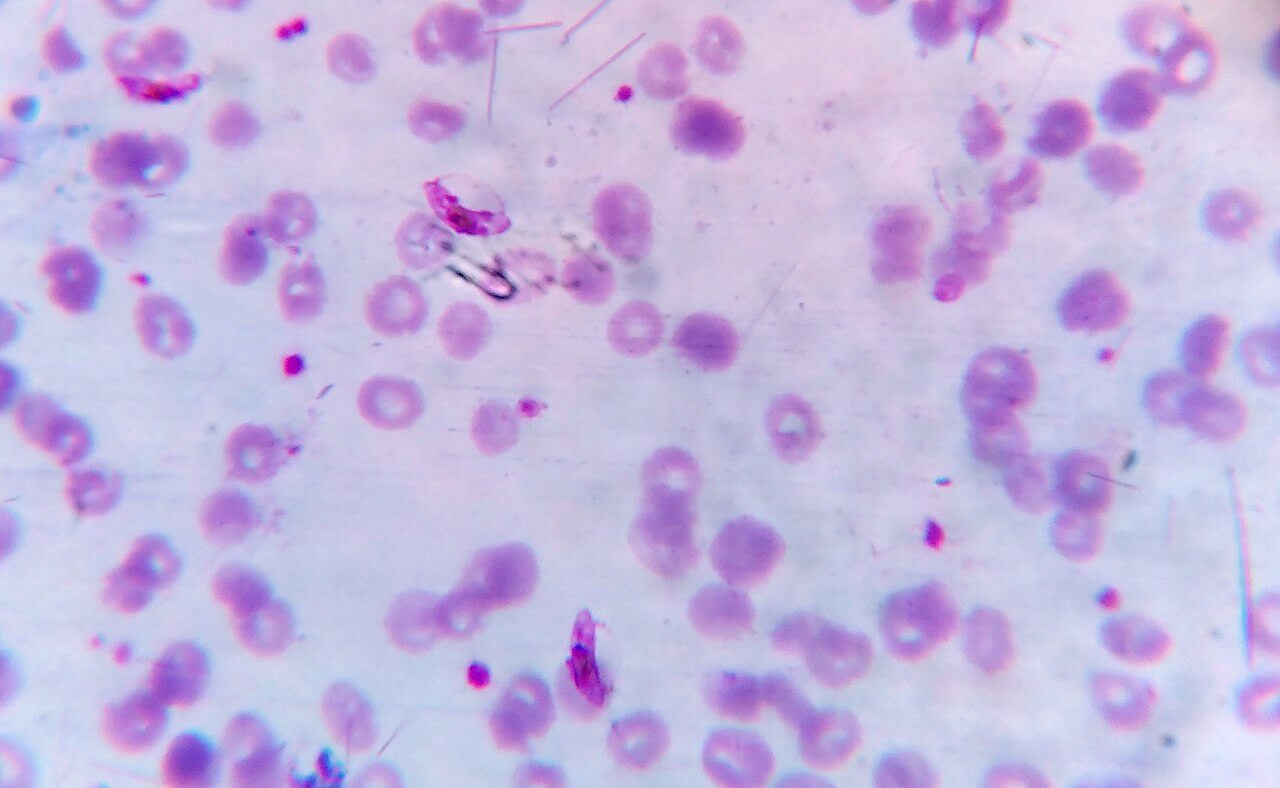

Symptoms of malaria include fever and flu-like illness, including shaking chills, headache, muscle aches, and tiredness. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may also occur. Malaria may cause anemia and jaundice (yellow coloring of the skin and eyes) because of the loss of red blood cells. Symptoms usually appear between 10 and 15 days after the mosquito bite. If not treated, malaria can quickly become life-threatening by disrupting the blood supply to vital organs. Infection with one type of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, if not promptly treated, may cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and death. In many parts of the world, the parasites have developed resistance to a number of malaria medicines.

That is from the excellent malaria.com. In short, yes, the most common symptoms are flu-like, but the symptoms can certainly go beyond that.

If you experience any flu-like symptoms while traveling in West Africa, it is important to get tested. Any clinic in the region will be equipped to test for malaria — it is one of the most common diagnoses made in this part of the world.

Is it possible to treat malaria?

Yes. Thank God. While there are many cases in West Africa where the dominant strain of malaria, p. falciparum, has been resistant to treatment with chloroquine, there are other drugs and types of combination therapy that continue to be effective.

Artemether/lumefantrine, a combination drug often sold under the trade name Coartem, is often prescribed for malaria treatment in most parts of West Africa. There are several other drugs, including Malarone and doxycycline, that are prescribed for treatment, and in severe or complicated cases, drugs may be administered intravenously.

Early diagnosis and treatment is critical

As a traveler, you do not have any baseline immunity that locals may have. Whether or not you are taking a prophylactic, the chances of malaria evolving into a severe or complicated case are much higher. And if you are not taking a prophylactic, the chances are higher still. Once again, any flu-like symptoms should be treated with urgency.

If you are going to be traveling in rural areas, buy a course of treatment before you go. I regularly travel with a full course of coartem when I am traveling around West Africa, and I will self-treat if I do not have access to a clinic. If I come down with flu-like symptoms, believe me, I am going to start popping those pills without hesitation. Coartem is not known for particularly worrisome side effects and the possible benefit of treating malaria early outweighs any possible cons.

Will I have malaria for the rest of my life?

The dominant strain of malaria in West Africa does not produce relapses if it is thoroughly treated. Strains that are more common in Asia and Central and South America can stay dormant in your liver for many years. P. falciparum does not do this. That said, if p. falciparum is not completely eliminated from the body during treatment, you could have a relapse. This is another reason why early treatment is imperative.

For additional information on Malaria, we highly recommend the CDC website and malaria.com, which regularly features questions from readers that are answered by a round table of doctors and researchers.

0 Comments